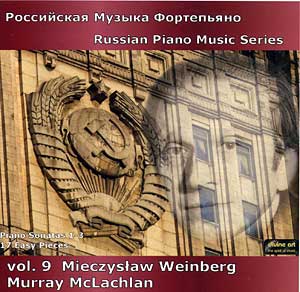

Russian Piano Music Series: Vol 9 – Mieczyslaw Weinberg

Piano Sonata No. 1, Op. 5 (1940)

Track 1 I Adagio

Track 2 II Allegretto

Track 3 III Andantino

Track 4 IV Allegro molto

Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 8 (1942)

Track 5 I Allegro

Track 6 II Allegretto

Track 7 II Adagio

Track 8 IV Vivace

Piano Sonata No. 3, Op. 31 (1946)

Track 9 I Allegro tranquillo 9.35

Track 10 II Adagio 7.27

Track 11 III Moderato con moto 5.36

17 Easy Pieces, Op. 34 (1946)

Track 12 No. 1 Merry March 0.20

Track 13 No. 2 The Nightingale 1.12

Track 14 No. 3 The Skipping Rope 0.29

Track 15 No.4 BabaYagll 0.22

Track 16 No. 5 Playmates 0.48

Track 17 No. 6 The Sick Doll 1.08

Track 18 No. 7 ATm Soldier 0.53

Track 19 No. 8 Grandmother’s Fairy Tale I .09

Track 20 No. 9 The Little Shepherd 0.53

Track 21 No. 10 Hide and Seek 0.35

Track 22 No. 11 Father Frost 0.53

Track 23 No. 12 MelancholyWaltz 1.05

Track 24 No. 13 The Goldfish 0.45

Track 25 No. 14 Petrushka’s Lament 0.35

Track 26 No. 15 Catch me if you can 0.13

Track 27 No. 16 The Dolls 2.04

Track 28 No. 17 Good Night 1.34

Total Playing Time: 70.37

About

Mieczystaw Weinberg (1919-1996)

Mieczyslaw Weinberg — who actually preferred the non-German spelling ‘Vainberg’ — was born in Warsaw in 1919, the son of a composer and violinist at a Jewish theatre. When he was only ten he began his musical career there as a pianist and music director; two years later he started piano studies at the Warsaw Conservatory. After the German invasion of Poland in 1939 he was forced to flee the country and he went to the USSR, initially to Minsk. There he attended composition classes at the conservatory for two years, but when the Germans attacked the USSR in 1941 he had to flee again: he spent the next few years at the opera house in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. In the meantime his family had been murdered – burned alive — by the Germans.

In 1943 Weinberg sent the score of his newly completed First Symphony to Shostakovich, asking for an opinion of the work. Shostakovich arranged for him to receive an official invitation to Moscow — of especial value in the war years — and thus their close friendship was born. From the end ofAugust 1943 until his death in 1996, Weinberg lived in Moscow, working as a freelance composer. From time to time he also made highly regarded appearances as a pianist — for instance, he performed alongside Galina Vishnevskaya, David Oistrakh and Mstislav Rostropovich at the premiere of Shostakovich’s Alexander Blok Songs.

Weinberg’s first wife belonged to a well-known Jewish family. Her father was the actor and director Solomon Michoels (his real name was Vovsi), the greatest Jewish actor in the Soviet Union, who was unforgettable as King Lear. Michoels was chairman of the Jewish Anti-

Fascist Committee (JAC), which supported the work of a large writers’ collective. Under the leadership of llya Ehrenburg and Vasily Grossman, the latter organization prepared a ‘record of dishonor’ in which the atrocities committed by the Nazis against Jews in various countries were documented. The authors, however, had failed to predict that anti-Semitic persecution would reach terrifying levels in the Soviet Union as well.

The respected Russian journalist Arkady Waxberg relates that publication of the ‘record of dishonor’ was forbidden; half of the contributors were arrested and either shot or sent to a gulag. A secret trial of the leaders of the JAC ended with the execution of fifteen of its members on 12th August 1952. With this information, Waxberg also supplies a plausible explanation for the fate of Michoels, who was murdered by the secret police in Minsk on 13th January 1948. Weinberg, too, could have suffered a gruesome fate: towards the end of the Stalinist era, on 6th February 1953 (six months after the above-mentioned trial), he was imprisoned. It was with a sigh of relief that Shostakovich could write to his friend Isaac Glikman on 27th April 1953: “In the past few days MS. Vainberg has returned home: he has informed me by telegraph.”

The date is significant (Stalin had died on 5th March and Weinberg’s release was probably a direct consequence), as is the fact that Shostakovich does not mention where Weinberg was returning from: such matters were not discussed openly — so much for the hypocritical Communist legend of the equality of the peoples. A Jewish artist in the Soviet Union did not exactly enjoy an easy life.

Weinberg was an extremely productive composer with an output ranging from a Requiem to circus music. He had a (perhaps not entirely fashionable) inclination towards large-scale, epic music; in this respect Mahler and Prokofiev were important role models. His musical style was extremely varied, however, and his richly-colored palette ranges from folk elements to dodecaphonic techniques. Folk-music elements were not only of Polish and Russian origin, but also Jewish and Moldavian (some of his ancestors had come from Moldavia).