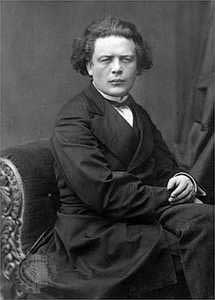

Anton Rubinstein (1829 – 1894)

Anton Rubinstein was born in 1829 at Vichvatijnetz a village on the river Dniester near the frontiers of Podolsk and Besserabia. His father was a Russian who obtained his modest income by leasing land in the Vichvatijnetz region. Anton was born into a large family and one of his earliest memories was of the entire family, including servants boarding a big covered wagon in order to move to Moscow.

Anton’s mother realised he was musical and devoted considerable time to his training. However he was not introduced to the works of the great masters and his studies were based on the compositions of Czerny, Clementi,Moscheles and Kalkbrunner. Eventually his mother arranged for Alexander Villoing, a well known piano teacher, to hear him play. Villoing was so impressed by Anton’s playing that he offered to teach him for nothing and Anton spent four years under his tutelage.

At the age of ten Anton gave his first public concert in Moscow and as a result of the enthusiastic reception it received, Villoing decided to take him on tour as a child prodigy. He toured in Europe and in 1840 played to Liszt and Chopin in Paris. He also played to the Grand Duke Constantine in the same year.

Liszt was very impressed and suggested that Villoing should take Anton to Germany to complete his studies at one of the best centres.

At this time almost all Europe was clamouring to hear virtuoso pianists and this presented marvellous opportunities for sponsers of child prodigies. As a result Rubinstein was exploited to the full in Norway, Sweden, Holland and other countries.

Because of this he did not have an opportunity to complete his musical education. In London he played to Queen Victoria and astonished the Court by his relaxed attitude and lack of embarassment in this most exalted of circles.

In 1843 Rubinstein returned to Russia where he was summoned to the Imperial Palace and asked to perform before Emperor Nicholas. He made many friends at the Palace and received many expensive gifts.

When child prodigies grow up they often lose most of the fascination that has to some extent obscured their imperfect musicianship and a fickle public has little time for young artists as soon as they cease to be popular. Unfortunately this was the lesson Rubinstein was to learn in his later teens.

In 1844 the family moved to Berlin and Anton succeeded in having one of his compositions (A Short Study for Piano) published. In 1846 Rubinstein moved to Vienna, mainly because he hoped for help from Liszt who was living there. In the event Liszt received him coldly and told him that: “a talented man must win the goal of his ambition by his own unassisted efforts.”

Life was difficult for Rubinstein in Vienna. He had many letters of introduction from the Russian Ambassador and his wife but the first few times he presented them they were of no help to him, so he opened one and read:

“To the position which we, the ambassador and his wife, occupy, is attached the tedious duty of patronizing and recommending our various compatriots in order to satisfy their oft-times clamorous requests. Therefore, we recommend to you the bearer of this one, Rubinstein”

Anton burned the remaining letters and commenced earning his living by giving cheap piano lessons in an attic. His creative instincts flourished in this period and he wrote hundreds of piano pieces and many of them became very popular over the course of time. He also wrote articles for a magazine but despite this he often lacked enough money to buy proper meals.

After about eighteen months Liszt decided to call on Rubinstein and was horrified at what he found. He treated Rubinstein to a meal and probably helped him in a number of ways.

In 1848 Rubinstein returned to Berlin and mixed with the Bohemian community of writers and artists. However there appeared to be little chance of making progress in Berlin so he decided to return to Russia. His manuscripts were confiscated by Russian customs officers because an anarchist had constructed a code which looked like music when written on ruled music paper. Six months later Rubinstein found the manuscripts in a second hand music shop. The owner explained that he had purchased them at an auction of waste paper.

Rubinstein settled in St Petersburg and earned his living by giving piano lessons. In 1852 the Grand Duchess engaged him as accompanist to the palace singers. Two years later he toured Germany, France and England. It was during this period that he published a magazine article stating that Glinka was comparable to Beethoven. His article received severe criticism from many sources.

However, Rubinstein steadily improved his position and in 1861 founded the Russian Musical Society at St Petersburg. This society became the nucleus of the St Petersburg Conservatoire which was established in the following year. Rubinstein was the first director of this institution and under his guidance daily concerts were given to raise funds and he did many things to establish the rights of professional musicians.

In 1867 Rubinstein’s volatile temper caused a serious dispute with the staff and he resigned to embrace the life of a travelling virtuoso. He played to large audiences in Europe and in 1872 embarked on a tour of the U.S.A. with the violinist Henri Wieniawski. They gave over 200 concerts but the American conception of a performer’s life – incessant money making – did not appeal to Rubinstein and prompted him to write:

“May Heaven preserve us from such slavery! Under these conditions there isno chance for art – one grows into an automaton simply performing mechanical work; no dignity remains to the artist, he is lost…”

Rubinstein often criticised the taste of his audiences and his attitude in this respect is perhaps best summed up by Brachvogel:

“No artist has ever shown to his audience so merciless a front. Both his programmes and his attitude are absolutely uncompromising. At first sight one is conscious of something stern, even inimical his bearing towards his audience, as though a chasm were fixed between them…but gradually the sense of hostility vanishes and the great artist conquers once and forever. Rubinstein has no idea of descending to the level of popular taste: he can onlyraise his audience to his own plane”

Rubinstein had married Viera Tchekuanov in 1865 and as a result of the financial success of the American tour he was able to purchase an estate in Peterho (In Russia). The couple eventually had three children.

In 1885-6 he gave a series of concerts illustrating the gradual development of piano music in a set of seven concerts. The complete set was played in each of the following cities:

St Petersburg, Moscow, London, Vienna, Berlin, Paris and Leipzig

Anton Rubinstein was reappointed to the position of Director of the St Petersburg Conservatoire in 1887. He formulated a new constitution for the conservatoire and drafted a plan to make each of the 52 governments of Russia responsible for musical education and to establish an opera in every major city. It is edifying to reflect that this ambition was eventually fulfilled by a communist government.

Bulow referred to Anton Rubinstein as “the Michelango of Music” and though he was frequently in dispute with other pianists there is little doubt as to his place in the list of all time great pianists. Today he is chiefly remembered for his innovatory ‘monumental’ style of pianism and his enormous recital programmes including the legendary series of “Historical Recitals” The nature of his differences with other musicians can be seen from the following quotations by Levensohn who was one of his contemporaries :

“His passionate temperament often carries him beyond the lawful boundaries: for instance, he takes too rapid a tempo in the prestissimo of Beethoven’sSonata Opus 109, hindering the listener from following in detail this desperate shriek from the soul: he always plays Chopin’s F major Ballade too rapidly…”

“..in Chopin’s Nocturne Opus 37 the heart -rending cry is interrupted by a succession of Palestrina-like chords. In Rubinstein’s rendering it is as if thesechords were played on the organ… these religious strains fail to sooth thesuffering soul and grief resumes its sway”

“…By this method the octaves are played with ease and freedom, whereas inthe rendering of other pianists one is always sensible of the effort. There is no living pianist who could imitate this”

In January1889 Rubinstein gave his final performance in Moscow. When he made his final bow to the audience he closed the piano and never made another public appearance